Will they build the Brenta cable car?

For many months this initiative aroused angry debate in Trentino. “The Brenta is a volcano” was the title of a five-column article in the Alto Adige newspaper. […]

The principle that drives everyone involved in this squabble is above all love for their local area, but obviously understood in different terms.

In a sense the story started fifteen years ago when a very young Scipio Merler emigrated to Canada in search of fortune, asking his father for just five hundred dollars to buy a small cement injection machine. Within twelve years those five hundred dollars had become three billion Italian lire.

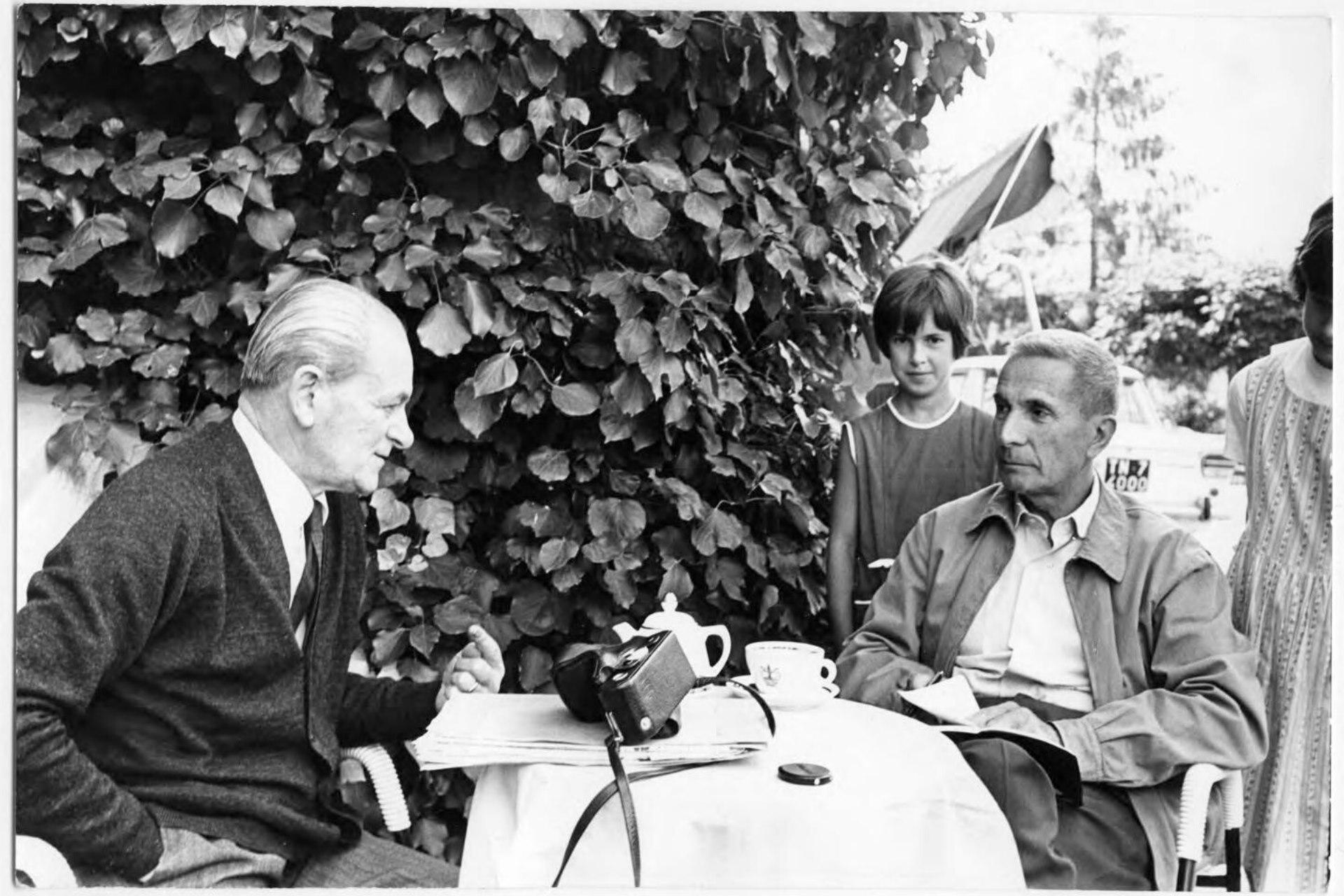

When he returned to Trento two years ago on holiday, Merler, always strongly attached to his homeland, met his friend Graffer and told him that he would like to do something useful and intelligent for Trentino.

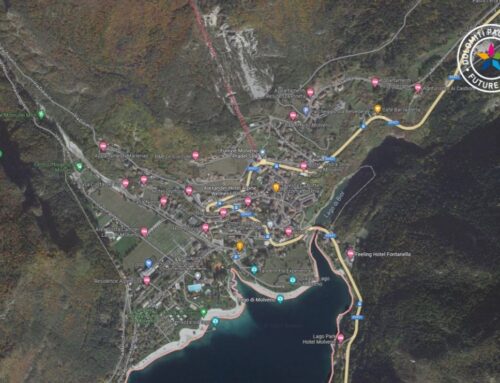

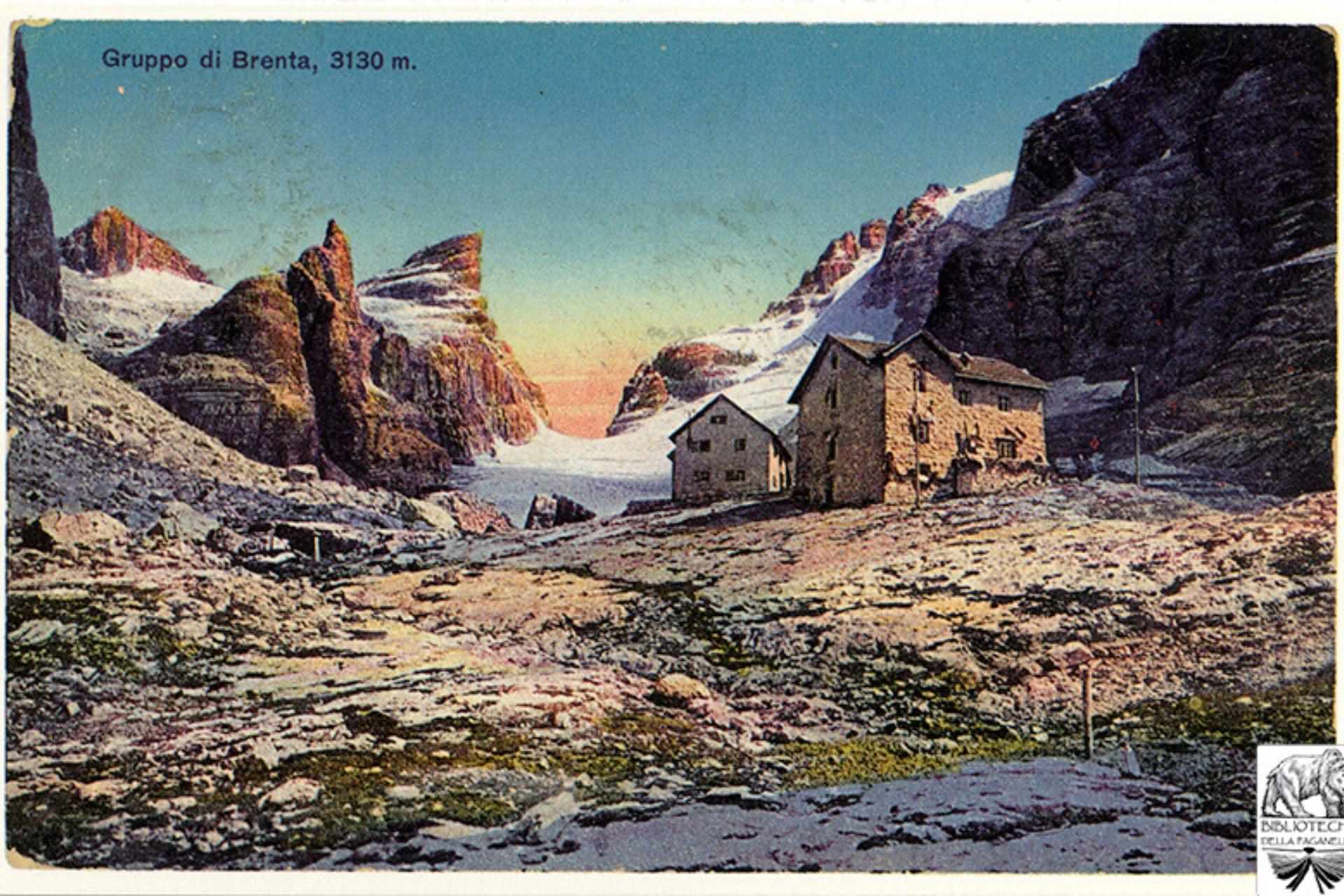

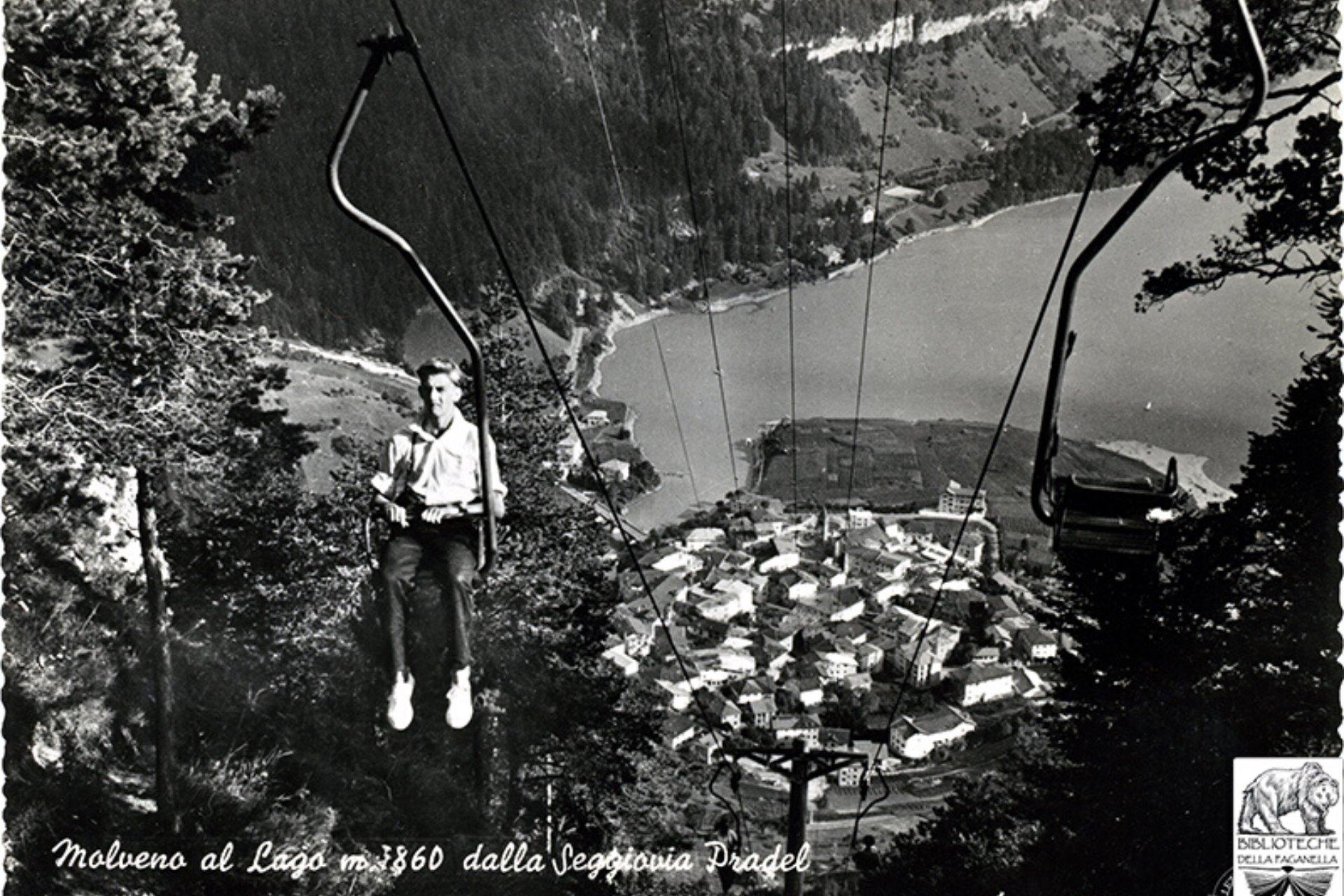

“Do you want something that will keep your name alive here for at least three or four generations?” replied Graffer immediately. “I can tell you straight away. Build a cable car from Molveno into the heart of the Brenta group, to the Rifugio Tosa. That would generate tourism in one of the most fabulous Dolomite ranges and breathe new life into Molveno, which ever since its famous lake was exploited and ruined for hydroelectric power, has seen in its summer season decline from five months to fifty days.” […]

And then the skies opened. As soon as the news spread there was an insurrection including: Italia Nostra, always ready to stand up when our natural, artistic, and traditional values are at risk; mountaineers of the SAT who saw their sanctuary at risk of mass invasion and industrial exploitation; the Trentino Natural History Museum; the Republican Party; the Socialist Party; various cultural associations; and even individual citizens.

Open letters, meetings, public debates, revelations, attacks and counterattacks in the newspapers, sudden shifts in one direction or the other, until last spring – when the first service cable car had already been set up – when professor Nicolò Rasmo, Superintendent of Fine Arts, intervened with a veto. The works were interrupted and Merler, somewhat disappointed, returned to Canada, where he remains to date.

Then on 6 April there was a “March on Trento” of almost the entire population of Molveno, including the elderly and children, numbering five hundred and arriving on busses. They marched peacefully through the city holding up placards protesting, for example: “You have never given us anything, at least give us a cable car”, “No cable car means hunger”, “Today is asking, tomorrow is shooting”, and “Bring our fathers back home from abroad”. (The day before, the provincial executive committee of the DC party had taken Molveno’s side.) […]

So, as far as somebody not in the know like myself can understand, having visited the site and heard the various factions, the issue stands as follows.

It is not possible to speak of disfigurement of the landscape, specially if the arrival station of the cable car, at the Bocca di Brenta pass at 2500 metres, is constructed inside a cavity.

But it is undeniable that by transporting three hundred people an hour up there, the cable car will spoil the charm and solitude of the natural environment.

The cable car would be of limited interest for skiing. From the intermediate station (in the Massodi area at 2200 m) upwards, as Graffer himself acknowledges in all honesty, a good ski run is impossible due to the conformation of the terrain. […]

A disconcerting aspect is the future presence up there of hundreds, even thousands of people unfamiliar with rocky terrain, who will wander off along the many Alpine paths cut into the sides of the cliffs, wonderful paths equipped with ropes and metal steps, but very exposed and vertiginous.

But the most serious hazard, as observed by Doctor Monaumi of Italia Nostra, does not lie in the cable car itself. The real problem is that the cable car might become the falling pebble that starts an avalanche, a landslide of further cable cars, chairlifts, ski lifts, restaurants, little hotels, refreshment points, and so on, infesting these marvellous mountains forever.

A conclusion? Perhaps a wise prophet, with his realistic and cheerful scepticism, is Dr. Marco Franceschini, a mountaineering academic who has also made numerous memorable climbing ascents including the Brenta range. He says: “It is pointless tilting at windmills. You have to defend sustainable positions, and certain developments cannot be avoided. Now the elections are approaching and everyone knows very well how these things go. Let’s put our souls to rest – like it or not, the cable car will be built. We should instead fight with all our strength so that the mountains do not go completely to rack and ruin”.

Corriere della Sera, 8 August 1967

Excerpt from I fuorilegge della montagna. Uomini, cime, imprese. Volume secondo: scalata, discese e gare olimpiche. Dino Buzzati. Edited by Lorenzo Viganò, 2012.

Thanks to the Paganella libraries for the photograhic material.